|

|

|

Home / Westbay Marine Village / Articles of Interest / Two

Solitudes

Two Solitudes Canadian

Living, July 1995 Canadian

Living, July 1995BY SANDRA MACKENZIE At

first glance, the differences in lifestyles are great:

one lives on the Fraser River in British Columbia,

the other in a century plus Ontario home. But the pioneering

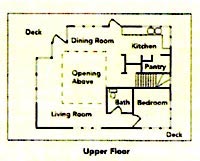

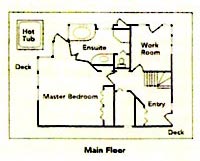

spirit that built Canada thrives in both settings About so years ago, builder Dan Wittenberg gambled that there were enough people who, like him, wanted to live in a water-based home but didn't want to forsake any of the comforts of a conventional landlocked residence. To that end, he developed Canoe Pass Floating Village, a marina development that is located on the estuary of the Fraser River, about 20 kilometres south of Vancouver. The idea was simple. While the water itself is owned by the Crown, residents would buy a portion of the adjacent upland, which would allow them to lease the water rights for their home and share the marina's facilities. The homes themselves would be built on land to meet all building codes, then anchored to floats that Wittenberg designed - stable, unsinkable, fireproof shells of reinforced concrete filled with Styrofoam and containing the homes' plumbing and electrical systems. The homes would then be launched much like boats and moored to the marina infrastructure.

In the beginning, Wittenberg had to convince several levels of bureaucrats, including financial institutions, building inspectors and environmental protection agencies, of the scheme's viability. Once those hurdles were cleared, there was an eager market ready to share his dream. To date, there are 43 homes in Canoe Pass and seven more in west Delta, B.C. Another 12 homes are under construction in west Delta. The floating community has attracted a broad cross section of purchasers, says Wittenberg. "We have young families and retired people living here. The only thing residents have in common is that they tend to be creative, imaginative people who prefer living on the water to mowing lawns." While there is no such thing as a standard Canoe Pass home, Wittenberg's residence is typical in its level of comfort, sophistication and individuality. Designed by architect Mark Ankenman, with interior design by textile artist Barbara Shelly, Wittenberg's wife, the two-storey house with a loft, an interior container garden and radiant-heat floors "dances to its own tune:' says Wittenberg. There is more truth than poetry in this description. Because the home moves with the tides and sways with the wave action, the house is never totally still. Usually the movement is gentle and soothing, but occasionally the effect is more disconcerting. "Fm prone to seasickness," he says, "so there are maybe two nights a year during really heavy storms when I have to go ashore to find a place to sleep"

Viewed from a distance, the 1,750-square-foot house, with its vivid scarlet roof and gingerbread trim, could be a fanciful reconstruction of a 19th-century riverboat. "There is an element of fantasy;" says Wittenberg. "Once you step onto your own wharf, into a floating home, you lose yourself in the rhythms of the river. There's a sense of leaving all your cares and woes on the land behind you."

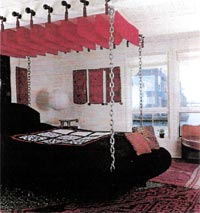

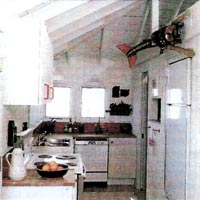

Life on the River THE ROLLING action of the home, in harmony with his suspended water bed, is as soothing as a rocking chair, says Dan Wittenberg. The bed's canopy (above) is a collage of embroideries from India. The galley kitchen (left) is compact yet efficient. Living on the water has its rewards. But before you sell your suburban villa and trade in the van for a kayak, there are a few things you should know. Although floating homes have a long and colorful history on the West Coast, many financial institutions are reluctant to provide mortgages for housing still perceived as unconventional. Moreover, there are few marinas that tolerate "live-aboards," whether they're bunking down in a highly mobile sailboat or living in an architect-designed home on a permanently moored barge, such as those built by Dan Wittenberg. Wittenberg had to seek approval from more than 30 different government agencies before his community could take shape. Cost, too, is a factor. Though Canoe Pass residents don't own land, they are inhabiting prized waterfront property, and their moorage costs reflect that reality. The house is built on land, but the sophisticated flotation structure is expensive. Depending on the size of the house, the cost of the floats can be more expensive than a traditional building site. But if the appeal of watching the salmon run past your front door, communing with a passing flock of wild swans or commuting by kayak outweighs the drawbacks, a home on the water just might be right for you.

|

||

|